Effective migration policy in the European Union (EU) depends on high-quality data. Yet EU migration and asylum statistics have long been plagued by inconsistencies and gaps. The 2015 refugee crisis starkly demonstrated the “pressing need for reliable, timely and comparable” migration data across member states (Singleton, 2016).

Accurate figures on migrants, asylum seekers, and border crossings are essential for crafting sound policies, allocating resources, and informing public debate. When data are fragmented or delayed, policymakers struggle to respond to emergencies and plan for the long term. In short, an integrated migration management database – one that harmonizes data collection and reporting EU-wide – is crucial for evidence-based decision-making.

The interactive dashboard below provides a comprehensive view of EU migration data across four dimensions. The Overview tab introduces key frameworks and challenges, Statistics visualizes trends from 2015-2022, Data Systems explains collection mechanisms, and the Timeline tracks policy evolution from 2001-2020.

EU Migration Data Dashboard

Overview of EU Return Migration

The return of illegally staying third country nationals is one of the main pillars of the EU's policy on migration and asylum. The EU Return Directive establishes common standards and procedures for the return of third-country nationals staying irregularly in Member States.

Key principles include:

- Prioritizing voluntary return over forced returns

- Ensuring procedural safeguards

- Respect for non-refoulement principle

- Proportionality in detention measures

The EU return policy is governed by several key legal instruments:

- EU Return Directive (2008/115/EC): Establishes common standards for returning irregular migrants

- Regulation (EC) No 862/2007: Defines statistics collection on migration and international protection

- Regulation (EU) 2020/851: Enhances data collection requirements for migration statistics

- European Convention on Human Rights: Guarantees fundamental rights protections

Despite efforts to harmonize return practices across the EU, several challenges persist:

- Low return rates compared to the number of return decisions issued

- Data inconsistencies between national and EU-level statistics

- Difficulties in cooperation with countries of origin

- Balancing effective return policies with human rights protections

- Issues related to non-returnable persons

- Varying implementation practices across Member States

- TCNs refused entry at external borders: Third-country nationals denied entry at EU borders

- TCNs found to be illegally present: Individuals detected as staying irregularly within EU territory

- TCNs ordered to leave: Individuals issued a return decision by authorities

- TCNs returned following an order to leave: Individuals who have been successfully returned

- Return types: Voluntary returns, enforced returns, and other return categories

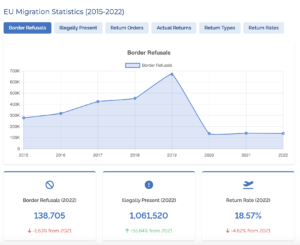

EU Migration Statistics (2015-2022)

EU-Wide Irregular Migration Data (2015-2022)

| Year | Refused Entry | Illegally Present | Ordered to Leave | Returned to Third Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 278,825 | 885,465 | 533,395 | 227,975 |

| 2016 | 318,998 | 924,035 | 493,785 | 250,015 |

| 2017 | 425,605 | 567,675 | 460,185 | 162,995 |

| 2018 | 454,975 | 575,425 | 456,660 | 145,905 |

| 2019 | 671,145 | 630,815 | 491,195 | 142,320 |

| 2020 | 137,965 | 559,355 | 400,215 | 71,070 |

| 2021 | 141,010 | 681,160 | 347,650 | 67,680 |

| 2022 | 138,705 | 1,061,520 | 423,680 | 78,690 |

Types of Returns (2015-2022)

| Year | Voluntary Return | Enforced Return | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 39,530 | 49,237 | 642 |

| 2016 | 46,796 | 39,906 | 272 |

| 2017 | 53,979 | 43,183 | 698 |

| 2018 | 53,652 | 49,364 | 6,356 |

| 2019 | 44,107 | 44,036 | 9,084 |

| 2020 | 24,430 | 24,549 | 9,426 |

| 2021 | 36,095 | 45,385 | 4,735 |

| 2022 | 43,145 | 49,865 | N/A |

Note: Data inconsistencies exist between national and Eurostat data. The significant drop in returns during 2020-2021 coincides with COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Return rates calculated as percentage of TCNs returned following an order to leave.

EU Migration Data Collection Systems

Eurostat is the statistical office of the European Union responsible for publishing high-quality Europe-wide statistics and indicators.

Role in migration data:

- Collects data from administrative records of national authorities

- Publishes standardized datasets, metadata, and national quality reports

- Provides the legal basis for the production of European statistics through Regulation (EC) No 223/2009

- Ensures data quality and comparability across Member States

The EMN was established by Council Decision 2008/381/EC to provide up-to-date, objective, and comparable information on migration and asylum.

Key activities:

- Publishing annual reports on migration and asylum developments

- Outlining political and legislative changes at national and EU level

- Contributing to policy-making through evidence-based research

- Facilitating public debate on migration issues

Data Collection Framework

The EU has established a comprehensive framework for data collection:

- Regulation (EC) No 862/2007: Established initial requirements for community statistics on migration and international protection

- Regulation (EU) 2020/851: Enhanced data collection by increasing frequency, adding breakdowns, and making more categories mandatory

- Technical Guidelines (2021): Provide detailed instructions for Enforcement of Immigration Legislation statistics

- International migration statistics (Article 3)

- International protection statistics (Article 4)

- Prevention of illegal entry and stay statistics (Article 5)

- Residence permits statistics (Article 6)

- Return statistics (Article 7)

- Quarterly return data (since 2021)

- Statistics on unaccompanied minors

- Definitional inconsistencies: Varying interpretations of key terms like "return decision"

- Double counting: Individuals may be counted multiple times when moving within Schengen

- Time lag: Gap between issuance of return orders and actual departures

- Data gaps: Missing or incomplete data from some Member States

- National variations: Different counting methodologies across countries

- Limited disaggregation: Insufficient breakdowns by age, gender, or vulnerability

National Data Collection Systems

| Country | Main Data Collection Actors | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), Federal Statistical Office (DESTATIS) | Decentralized system with variation across states (Länder) |

| Greece | Hellenic Police, Ministry of Migration Policy | Inconsistencies between annual and quarterly data; allegations of unreported practices |

| Poland | Office for Foreigners, Border Guard | Different methodologies between border and immigration agencies |

| Sweden | Migration Agency, Police Authority | Limited disaggregation; challenges in irregular migration assessment |

| Netherlands | Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND), Repatriation and Departure Service (DT&V) | Discrepancies between national and Eurostat statistics |

EU Return Policy Timeline (2001-2020)

EU begins work on a framework for common analysis and improved exchange of statistics on asylum and migration

Council Regulation (EC) No 862/2007 establishes Community statistics on migration and international protection

EU Return Directive (2008/115/EC) establishes common standards and procedures for returning irregular migrants

European Migration Network (EMN) is formally established by Council Decision 2008/381/EC

Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration emphasizes importance of data collection

Regulation (EU) 2020/851 enhances data collection requirements, including quarterly returns data

COVID-19 pandemic leads to border closures and significant impacts on migration patterns and return operations

As the dashboard illustrates, the EU has established sophisticated frameworks for migration data collection. However, examining the underlying systems reveals three critical problems that undermine the reliability of these statistics

1. Inconsistent Data Collection and Reporting

Migration data in the EU are collected by individual member states, leading to a patchwork of methods and definitions. Despite a common EU regulation on migration statistics (Reg. 862/2007) that aligned the broad definition of a migrant (generally, someone changing usual residence for ≥12 months), implementation varies. For example, Sweden and the United Kingdom (pre-Brexit) both applied the one-year residency criterion, but Sweden uses a continuous population register while the UK relied on a sample passenger survey to estimate migration (Raymer et al., 2011). Other countries use different concepts: Romania historically counted only permanent moves as migration and maintained separate registers for citizens and foreigners (Raymer et al., 2011). Such divergent practices – registers vs. surveys, differing residency intentions, or separate tracking for nationals – result in non-comparable datasets. In effect, what qualifies as an “immigrant” or “emigrant” can differ by country. This inconsistency is compounded by variations in enforcement: some states require residents to register moves (often under penalty), while others have looser requirements. Undercounting is a serious issue where reporting is not enforced. A recent demographic study found the highest undercounting of migration events in several newer EU member states – particularly Bulgaria, Latvia, and Romania – due to people not officially registering departures or arrivals (Dańko et al., 2023). However, undercounts are not exclusive to the East; even countries considered to have robust statistics showed notable gaps in certain periods (Dańko et al., 2023). This suggests that no EU country is completely immune to data quality problems.

Differences in data reporting also arise in how countries submit information to EU agencies. Eurostat collects annual migration statistics from national statistical institutes, but the level of detail varies. Some provide breakdowns of immigrants by origin country and emigrants by destination, while others fail to disaggregate, especially after regulatory changes. In fact, after new EU definitions were introduced around 2008, fewer countries provided detailed origin/destination breakdowns, reducing data completeness for those years. In other words, even as definitions were harmonized on paper, some national systems could not meet the new reporting demands, leading to patchy data. Additionally, EU agencies maintain separate databases – e.g. Frontex tracks irregular border crossings and returns, EASO (now EUAA) compiles asylum application figures, and Europol/eu-LISA handle visa and security databases – each with their own data streams. Without integration, these siloed systems risk inconsistencies or double-counting. Overall, the lack of a unified data collection mechanism has produced a mosaic of national statistics that are often not directly comparable or easily merged.

2. Data Quality and Harmonization Issues

The quality of migration data across the EU is uneven. Many member states struggle to capture emigration (outgoing migration) accurately, resulting in unreliable net migration figures. As one analyst observed, emigration or departure data are “very weak in most” EU countries (Singleton, 2016). People leaving a country often do not notify authorities, especially within the free movement area, leading to official figures that under-report departures. This can give a false impression of population growth or retention. On the immigration side, some countries did not initially count certain groups (e.g. asylum seekers or temporary migrants) in their population statistics, causing gaps in coverage. Efforts to harmonize have made progress – Eurostat reports indicate that by the late 2010s most EU countries had adopted the 12-month residency definition and improved coverage of various migrant groups (European Commission, 2021). The use of population registers has expanded, which should, in theory, increase. Nevertheless, harmonization remains a work in progress. Some countries use the intended duration of stay (when a person registers, they declare if they intend to stay ≥1 year) while others use observed duration (counting migrants only after they have actually stayed 12 months) (International Migration statistics). These methodological nuances can lead to different timings and totals in the data, even if the legal definition is aligned.

Another challenge is timeliness and consistency. Migration data are often published with significant lags – annual immigration/emigration statistics might be released a year or two after the fact. During rapidly changing situations (such as surges in asylum claims or sudden outflows due to COVID-19 or Brexit), the standard data cycle has proven too slow and infrequent. The European Commission noted that current data collection frequency is “not sufficient to provide adequate information” on fast-changing migration dynamics, and that more timely and detailed stats are needed (European Commission, 2021). When official data are delayed, countries sometimes release provisional figures or different agencies provide overlapping numbers (e.g. police vs. statistical office counts of arrivals), which can cause confusion. Coherence between datasets is another issue – ensuring that asylum data, residence permit data, and population migration figures line up. Eurostat has worked with countries to improve cross-domain coherence (e.g. reconciling asylum seeker counts with subsequent population inclusion) (European Commission, 2021). But inconsistent practices still lead to discrepancies; for instance, an individual granted asylum might be counted in asylum stats but the timing of when they appear in immigration stats can vary by country. All these factors – definitional drift, undercounting, reporting delays, and fragmentation – undermine the harmonization of EU migration data. While the EU’s statistical system is more robust than in past decades, “significant gaps between immediate policy needs and data availability remain” (Singleton, 2016).

3. Impact of Data Inconsistencies on Policy Decision

In today’s data-driven world, policymaking increasingly relies on solid statistical evidence. However, in the complex realm of EU migration policy, the numbers don’t always tell a clear story. Recent research reveals how inconsistencies in migration data create significant challenges for policymakers, affecting everything from crisis response to public trust.

Imagine trying to coordinate emergency response efforts with an incomplete picture of the situation. This is precisely what EU policymakers faced during the 2015 refugee crisis. As Singleton (2016) points out, there’s an inherent tension between getting timely data and ensuring its accuracy. When thousands of people are crossing borders daily, decisions can’t wait for perfect information, yet hasty responses based on unreliable data can lead to ineffective policies.

The problem becomes even more complex when different countries report contradictory numbers. During the 2015 crisis, some countries reported dramatically different asylum application numbers for the same groups due to secondary movements or double-counting (Gökalp Aras et al., 2024). Without a unified system for real-time data sharing, policymakers often had to make crucial decisions about resource allocation and emergency response based on partial or conflicting information.

The impact of data inconsistencies extends far beyond crisis management. Consider the challenge of allocating EU funds like the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF). When countries underreport their migration inflows, they might receive less support than they actually need (Gökalp Aras et al., 2024). Similarly, if a country underestimates emigration, it might over allocate resources to services that end up being underutilized.

These issues become particularly evident in labor migration policies. How can governments set appropriate quotas for work visas when they can’t accurately track current migration patterns? As highlighted in recent studies, inconsistent figures make it nearly impossible to assess whether policy changes actually affect immigration rates or if observed changes simply reflect differences in data collection methods (Gökalp Aras et al., 2024).

Perhaps the most concerning impact is on public trust and democratic discourse. In an era of increasing skepticism toward official statistics, inconsistent migration data provides fertile ground for misinformation. Media outlets sometimes misuse statistics, for instance, by adding up border crossing detections from different points without accounting for multiple counting of the same individuals (Singleton, 2016). The problem compounds when different official sources show conflicting trends. When Eurostat data tells one story and national figures another, public confidence in both sources erode. This undermines the legitimacy of policy decisions and makes it harder to build consensus on migration issues (Gökalp Aras et al., 2024).